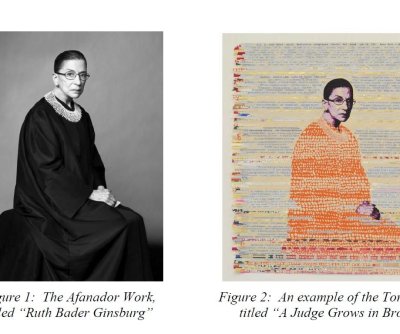

A federal judge has sided with an artist who used a photograph of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her art without the permission of the photo agency that sued her. Photo courtesy of U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia

March 18 (UPI) — A federal judge has sided with an artist who used a photograph of Ruth Bader Ginsburg in her art without the permission of the photo agency that sued her.

Creative Photographers Inc. filed a lawsuit in 2021 against Julie Torres for using a 2009 portrait of Ginsburg in more than a dozen silkscreen prints and mixed media works, court documents obtained by UPI show.

Each work sold for up to $12,000 and her artwork was displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, according to the lawsuit.

Ruvén Afanador, the photographer who took the photo of the late Supreme Court justice, has an agreement with Creative Photographers — which serves as the exclusive agency for his work.

Afanador, who was not a party to the lawsuit, maintains the copyright for the photograph. Creative Photographers obtained the certification of registration with the U.S. Copyright Office for the work on Afanador’s behalf.

The news comes ahead of two similar cases that could have a profound impact on such copyright cases: the highly expected decision from the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of The Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts v. Lynn Goldsmith, and another by a new federal tribunal created to address such claims between lesser-known artists.

Questions of exclusive rights

Torres had argued that the case should be dismissed on the ground that Creative Photographers did not have legal standing under the Copyright Act and that, even if the agency does have legal standing to sue, it failed to state a required claim to relief because her works are protected by fair use doctrine.

U.S. District Court Judge J.P. Boulee agreed with Torres in his decision Monday, stating that the U.S. Copyright Act and existing case doctrine show that a party without an ownership interest in a work, or without being an exclusive licensee, does not have legal standing to sue.

“A ‘transfer of copyright ownership’ occurs when a copyright owner conveys an exclusive license ‘of any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright,’ but a transfer of ownership does not occur when that owner conveys only a nonexclusive license,” Boulee wrote.

“Because a nonexclusive license does not convey an ownership interest, a nonexclusive licensee does not have standing to sue for copyright infringement.”

Boulee said that the terms of agreement between Afanador and Creative Photographers “plainly reserves ownership of the copyright in Afanador” and thus the court sought to determine whether Creative Photographers had standing as an exclusive licensee.

“Legal authority on this question — does an agreement appointing an entity as a copyright owner’s exclusive agent provide statutory standing to sue for infringement? — is few and far between,” Boulee noted.

Case of the Cabbage Patch Kids

Boulee largely based this determination on a 1987 case argued before the Eleventh Circuit between the manufacturers of Cabbage Patch Kids toys and another company — Schlaifer, Nance & Co. — that obtained “the exclusive worldwide rights” to license the designs.

The toys were then sold by the company Coleco Industries as Cabbage Patch Kids. However, the manufacturer began selling a new product called the “Furskin” bear and negotiated the contract for its sale directly to Coleco.

Schlaifer, Nance & Co. alleged that the Furskin bear was a derivative product of the Cabbage Patch Kids and thus would be covered under its exclusive license. The court at the time determined that the agreement between the two companies was a mere contractual right and not a right enforceable under the Copyright Act.

Boulee said that while Creative Photographers tied its claim to specific provision of the Copyright Act, the court found that the language of the agreement with Afanador did not “explicitly and conclusively” grant the agency right of exclusivity as defined under that provision.

However, Boulee has allowed Creative Photographers to rework its complaint and the company has 14 days to file the amended document.

U.S. Supreme Court and a new tribunal

The ruling comes ahead of a highly expected decision from the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of The Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts v. Lynn Goldsmith.

The Supreme Court last year heard arguments in a copyright case stemming from silk-screen prints by late pop artist Andy Warhol of the late musician Prince that were based on a portrait of the singer taken by renowned photographer Goldsmith.

Goldsmith, known for taking portraits of famous rock musicians, had taken the portrait of Prince in 1981. When Prince released his album Purple Rain three years later, taking him to mega-stardom, the magazine Vanity Fair spent $400 to license Goldsmith’s photo for use as an artist’s reference.

Vanity Fair then commissioned Warhol, the artist known best for appropriating images from pop culture such as Campbell’s soup cans and portraits of Marilyn Monroe, to make a silk-screen print based on the photo of Prince, according to documents filed to the Supreme Court.

Goldsmith said in court documents that she was unaware that the image was to be used by Warhol and that the artist would continue to use her photograph to create a total of 16 works, including paintings and drawings, known collectively as the Prince Series.

When Prince died in 2016, Condé Nast magazine used one of Warhol’s prints based on Goldsmith’s photo on the cover of its issue paying tribute to the late musician. Warhol died in 1987.

Nearly two dozen briefs have been filed by groups including Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the American Society of Media Photographers and the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, taking various sides in the legal fight.

The U.S. Copyright Office, which is responsible for advising the courts and the public on copyright matters, also filed a brief tied to the Warhol case in support of Goldsmith, asserting that the photographs were not fair use and that Warhol’s prints did not create new expressive meaning.

In another similar case, a Massachusetts photographer named Cheryl Miller filed a claim for infringement against a New York artist who replicated her photograph as a painting.

Miller filed her claim with the Copyright Claims Board, a tribunal established by law in 2020 to provide an alternative to federal court which could revolutionize how artists challenge copyright violations.

The tribunal was established by the Copyright Alternative in Small-Claims Enforcement Act of 2020 to allow creators a small claims court-style system to challenge copyright violations.

If Miller is successful with her claim, it could demonstrate the power of pursuing such claims with the CCB for small creators seeking damages when their copyrights are violated.

If Ladson is successful with his defense, small artists could feel empowered to use the work of photographers as reference material in their work without fear of legal repercussions.

0 Comments :

Post a Comment