Online News Magazine

More than 200,000 people have already died because of COVID in the U.S. in 2022, and President Joe Biden’s administration is bracing for 30,000 to 70,000 more deaths this winter. A bad flu year, in comparison, brings about 50,000 deaths.

Yet public funding has dwindled or vanished for the very vaccines and treatments that have lowered the risk of COVID death. In the next four months or so, these key tools will only be available to those who can afford them on the private market as current federal subsidies dry up—a situation that could affect access and uptake. “It’s scary to think about what happens when there’s a next surge if those things don’t come back,” says Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, a demographer and sociologist at the University of Minnesota.

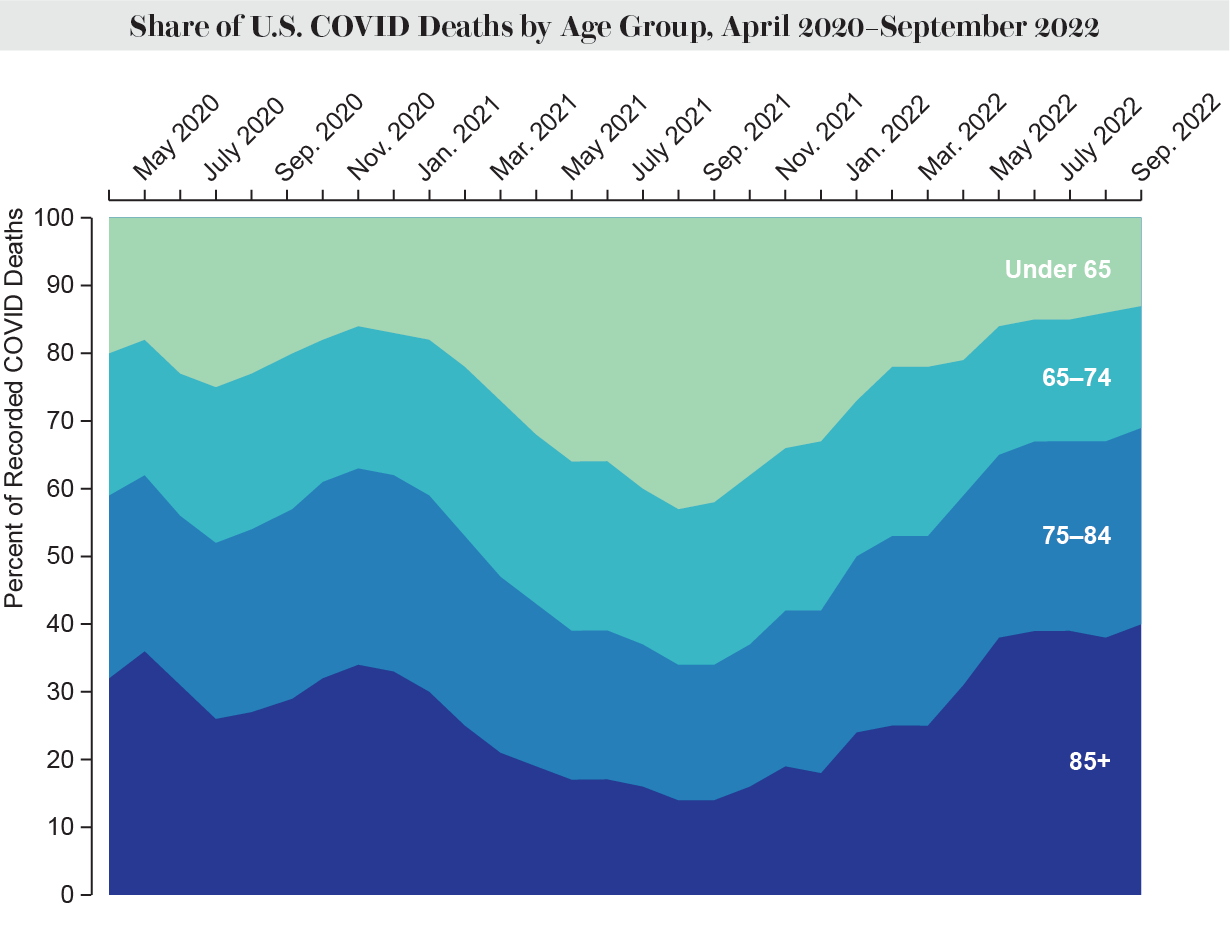

At the peak of the most recent surge of fatalities in August, 91.9 percent of all deaths around the country were among people 65 and older—the biggest share of any surge in the pandemic, even higher than in April 2020.

Long-term care facilities were hit extremely hard during the pandemic, with residents and staff accounting for about one fifth of all COVID deaths. In 2021 vaccinations and treatments helped lessen these blows. But COVID deaths in nursing homes have now risen again. From April to August this year, this number more than tripled.

Although most COVID deaths are among the elderly, younger people are still dying at higher rates than usual because of the illness—especially those who work in essential fields, research shows. Under normal conditions in the U.S., “younger people rarely die,” says Justin Feldman, a visiting scientist at the Harvard François-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, who studies social inequality. But now, he says, “excess mortality for all age groups is quite high and uniquely high in the U.S., compared to other wealthy countries.”

When it comes to race and ethnicity, as well as geography, other patterns are emerging as well. But experts note that such changes are likely to be temporary.

Each fall COVID mortality rates among white people have edged closer to or higher than those among Black people. But deaths of racially minoritized people have jumped again during surges, when the total COVID death rate climbs. Experts expect the same pattern of inequity in future surges. “White people are dying at higher rates during particular time periods when the total death counts are lower. And Black people are dying at higher rates during other time periods when death counts are higher,” Feldman says. “And that’s not even acknowledging American Indians, Alaska Natives and Pacific Islanders, who’ve had consistently the highest death rates this entire time, at every point in time, and often are excluded from these kinds of analyses.”

Two years into the pandemic, deaths from all causes were higher for Indigenous peoples and Pacific Islanders, compared with pre-COVID levels, according to a study published in September. Changes in life expectancy have also hit people of color harder. Black, Hispanic and Indigenous people in rural areas had the deadliest 2021 from COVID among all relatively large racial or ethnic groups in the U.S., according to a preprint paper that has not yet been peer-reviewed. These disparities are often exacerbated in rural areas with poorer access to health care and an older and sicker population—and frequently lower vaccination rates.

COVID vaccines have helped reduce some disparities. “Vaccination shrinks racial inequality,” Feldman says. “It’s that simple.” But the same factors putting many people of color at risk, including racism and systemic oppression, persist. For example, booster access in communities of color has been inequitable, driving death rates higher.

Being unvaccinated is still a major risk factor for dying from COVID. In August 2022 unvaccinated people died at six times the rate of those who got at least the primary series of the vaccine, according to the CDC. And unvaccinated people age 50 and older were 12 times more likely to die than vaccinated and double-boosted peers.

Because a large portion of the U.S. population has at least one COVID shot, the majority of deaths are now among vaccinated people. In July 59 percent of COVID deaths were among the vaccinated, and 39 percent were among people who had one booster or more. That doesn’t mean the vaccines are not working anymore; they are still highly effective at reducing the risks of severe illness and death. But their efficacy wanes over time, and continued boosters need to be combined with other precautions to prevent illness and death. In August, people age 50 and older who were vaccinated and had just one booster were three times more likely to die than people with two or more boosters, according to the CDC.

Only 10.1 percent of Americans age five and older have received the relatively new bivalent booster, which is highly effective against the Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID. More than 14 million Americans 65 or older (or nearly 27 percent) have gotten the updated jab—a higher rate than among younger Americans but nothing like the uptake for the initial two doses. “We’ve never had the same kind of efforts to make boosters available and accessible the way that we did primary series vaccinations,” Wrigley-Field says. Boosters are critical not just to reduce hospitalization and death for everyone but also to weaken chains of transmission and help protect the most vulnerable.

Antiviral drugs and monoclonal antibody treatments, both of which can be extremely effective at preventing hospitalization and death, are also underused and inequitably distributed. Zip codes with the most vulnerable people have the lowest uptake of antivirals despite having the most dispensing sites, one CDC study found. Another CDC study showed that people of color are less likely than white people to receive monoclonal antibodies. Between May and early July, only 11 percent of people who tested positive for COVID reported being prescribed antivirals. Notably, those with higher incomes received the highly effective antiviral Paxlovid at more than twice the rate of those with lower incomes, according to another study. An estimated 42 percent of U.S. counties were “Paxlovid deserts” as of March, according to one analysis from a medication-dispensing site.

About 8.7 million Americans are immunocompromised, putting them at greater risk of death from COVID. Yet only about 5.3 percent of them have received Evusheld, a treatment that can prevent severe outcomes for six months at a time, the CDC estimated in September.

“We’re still in the middle of this crisis,” Urquiza says. “The most vulnerable will not just be left behind but will be sentenced to death.”

This might seem like a story about numbers. It’s not. It’s a story about people. Many of their stories have been compiled by Alex Goldstein, founder of Faces of COVID, an online project established to show the stories behind the statistics—and to honor the lives lost and those who grieve them. “We all lost something when your loved one died,” Goldstein says. “My biggest fear has always been that if we fail to learn the lessons of this pandemic, which I believe we are in the process of doing, we will be hit 10 times harder by the next one,” he adds. “I think we’re proving ourselves to be completely unable to wrap our arms around those types of challenges. And that scares me for the future.”

0 Comments :

Post a Comment